Content |

|---|

Description:

29 cm.. length and 320 g. of weight.

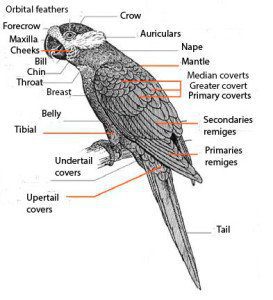

The Puerto Rican Parrot (Amazona vittata) has the forecrown and lores, red; rest of the head and nape, feathery green grass bordered with black color, giving a strong intricate scaly appearance.

feathers of the the mantle grass-green; back and scapulars with less pronounced dark margins; rump and uppertail-coverts, paler, more green-yellow. The large external coverts they are blue; rest of the coverts color green grass. Primaries and outerweb of the outer secondaries, blue; the innerwebs of the external side and secondary internal, green. Under, the wings They are green and flight feather bluish green.

Underparts green stained yellowish; feathers throat and the chest with dark edges. Upper, the tail is green; below is more yellowish, with its end yellow; both with outerweb blue towards outer feathers. Bill color pale horn; brown the irises; legs pale grey.

Both sexes similar. Immature adult-like, but with the bill light yellow with gray on the basis of upper jaw.

- Sound of the Puerto Rican Parrot.

Description 2 subspecies:

-

Amazona vittata gracilipes †

(Ridgway, 1915) – Extinct. Of smaller and with feet smaller and thinner than the species nominal.

-

Amazona vittata vittata

(Boddaert, 1783) – Nominal.

Habitat:

Video – "Puerto Rican Parrot" |

|---|

The Puerto Rican Parrot formerly he frequented the main types of natural vegetation (various forest habitats, from mangroves to montane forests) in Puerto Rico, with the possible exception of dry forests in the southern coastal regions.

Its Current small population remainder inhabits the mountain rainforest to 200-600 m. In the lower mountain slopes dominated by trees tabonuco of the species Dacryodes excelsa, in swampy forests at higher elevations characterized by the abundance of Cyrilla racemiflora and areas Sierra palm Prestoea montana.

Observed in pairs or (especially when they fed) in small flocks, having formed, formerly, flocks of several hundred.

Reproduction:

The Amazona Puerto Rican nidifican in large and deep cavities of trees; in the past they put their nests in the limestone hollows, in the west of the island. The amazon of Luquillo usually nest in species Cyrilla racemiflora. They defend their territory aggressively in the vicinity of the nest while playing. The egg laying, between February and April, possibly to coincide with the availability of fruit. Clutch 2-4 eggs (usually three).

Since 2001, all nesting known in the wild they have occurred in artificial cavities (White et al ., 2006).

Food:

The diet of the Puerto Rican Parrot It consists of a variety of fruit, seeds, flowers and leaves, among which include fruit of Prestoea montana and Dacryodes excelsa, flowers of Piptocarpha tetrantha and bracts of Marcgravia sintenisii.

Distribution and status:

Size of its range (breeding/resident): 1.000 km2

The Puerto Rican Parrot It is endemic to Puerto Rico and the former neighboring islands Mona and Snake; there are reports of parrots Vieques and St Thomas, probably belonging to this species. Formerly found in all forested regions Puerto Rico (with the possible exception of dry coastal strip south), but from around 1960 their habitat was limited to the Luquillo forest, in the East.

drastic population decline and rank the mid-nineteenth century. The pre-European population was probably hundreds of thousands of birds. There was a dramatic decline, which it reduced its population to about 2.000 copies in 1937 and in 1950 they were only a 200: a search in 1968 only revealed the existence of 24 birds.

The conservation program, initiated in 1968, It includes captive breeding, the provision of nests, detailed investigation ecology and reproductive biology and the control predators and competitors.

In 1992 the wild population was 39-40 birds 58 in captivity (all in Puerto Rico). Its population has declined, to near extinction, mainly by habitat loss (in 1912 only 1% the virgin forests of the island they remained), the hunting and capture as pets. The continuing threats to the tiny remaining population include impact of hurricanes (wild population halved to 21-23 after the passage of birds hurricane Hugo in 1989), competition with introduced bees Apis mellifera by tree cavities, the loss of broods due to parasitic flies Philornis pici, losses caused by predators and competition for nesting cavities with Pearly-eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus). The Puerto Rican Parrot, inhabitants of the Culebra island (dubiously separated as subspecies Amazona vittata gracilipes), extinguished early twentieth century, probably because of persecution due to damage of crops and the impacts of hurricanes. existing population protected inside of the El Yunque National Forest.

Description 2 subspecies:

-

Amazona vittata gracilipes †

(Ridgway, 1915) – Extinct. Culebra Island (Puerto Rico).

-

Amazona vittata vittata

(Boddaert, 1783) – Nominal.

Conservation:

State of conservation ⓘ |

||

|---|---|---|

critically endangered ⓘ (UICN)ⓘ

critically endangered ⓘ (UICN)ⓘ

| ||

• Current category of the Red List of the UICN: critically endangered.

• Population trend: Increasing.

• Population size: 33-47.

Rationale for the Red List category

Once you have done a count of birds, are only 13 Puerto Rican Parrot in the nature, leaving the species on the verge of extinction. The conservation action the population has increased from 1975, but remains critically endangered because the number of mature individuals is still minuscule. If the released birds breed successfully in nature and the figures remain stable or increase, the species can justify a change of state in the future.

Justification of the population

From 2011, the population was between 50-70 individuals divided into two areas, approximately equivalent to 33-47 mature individuals. In 2013, its population had only increased to 80-100 individuals in the nature (64-84 in Down river and 15-20 in The anvil). But, since the released birds are not counted as mature individuals until they have successfully bred in nature (UICN 2011), and the entire population of Down river It is derived from released birds. The total number of mature individuals is uncertain but may well be less than 50, therefore, estimating 2011 of mature is maintained in this figure.

Justification of trend

It is estimated that increase 1-19% has occurred in the last ten years, based on regular accounts of the total wild population.

The Puerto Rican Parrot in captivity:

According to sources, A copy of Puerto Rican Parrot lived 10,1 years in captivity. But, considering the longevity of similar species, likely maximum longevity is underestimated in this species. In fact, it has been reported that They can live up to 27,2 years in captivity, what it is plausible but has not been confirmed. Taking into account that the Cuban Parrot (Amazona leucocephala), closely related, You can live up 50 years (Wilson, et to the., 1995), an age close to the latter figure may be possible for the Puerto Rican Parrot.

Each captive specimen of this species which is capable of reproducing, must be placed in a well-managed captive breeding program and not sold as a pet, in order to ensure its long-term survival.

Alternative names:

– Puerto Rican Amazon, Puerto Rican Parrot, Red-fronted Amazon, Red-fronted Parrot (English).

– Amazone à queue courte, Amazone de Porto Rico (French).

– Puertoricoamazone, Puerto-Rico-Amazone (German).

– Papagaio-de-porto-rico (Portuguese).

– Amazona Portorriqueña, Amazona Puertorriqueña, Cotorra de Puerto Rico, Cotorra Puertorriqueña (español).

scientific classification:

– Order: Psittaciformes

– Family: Psittacidae

– Genus: Amazona

– Scientific name: Amazona vittata

– Citation: (Boddaert, 1783)

– Protonimo: Psittacus vittatus

Images Puerto Rican Parrot:

Sources:

– Avibase

– Parrots of the World – Forshaw Joseph M

– Parrots A Guide to the Parrots of the World – Tony Juniper & Mike Parr

– Birdlife

– Photos:

(1) – Amazona vittata – Photo via Good Free Photos

(2) – A Puerto Rican Amazon By Pablo Torres of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region (PRParrot_cototrapuertorriqueña byPablo Torres) [Public domain or CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

(3) – A Puerto Rican Amazon at Iguaca Aviary, Puerto Rica By Tom MacKenzie ofU.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region (Puerto Rican parrot 4) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

(4) – A Puerto Rican Amazon at Iguaca Aviary, Puerto Rica By Tom MacKenzie of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region (Puerto Rican parrot 4) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

(5) – A pair of Puerto Rican Amazons See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

(6) – A Puerto Rican Amazon at Iguaca Aviary, Puerto Rica By Tom MacKenzie of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region (Puerto Rican Parrot by Tom Mackenzie) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

(7) – Amazona vittata – Author: Mike Morel, USFWS – pixnio

(8) – Flying Parrot, blue feathers visible By Tom MacKenzie [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

(9) – A Puerto Rican Amazon at Iguaca Aviary, Puerto Rica By Tom MacKenzie of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region (Puerto Rican parrot 1) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

– Sounds: Eric DeFonso, XC173411. accessible www.xeno-canto.org/173411